Water Data Cannot Fix Broken Behavior

In a recent New York Times editorial, Charles Fishman argues “Water is Broken. Data Can Fix It.” He laments the dearth of water data in the United States, and suggests that increasing the collection and availability of water data will create a demand for additional information, change behavior, and ignite innovation. Mike Kiparsky and Joshua Viers reiterate this idea in the Los Angeles Times, in the context of needing better information for California water.

I cannot argue against the need for more and better data, made available in formats that support decision-making at multiple levels. I would even agree with both articles that current water data does not provide all the information we need, although there are certainly a number of extensive databases available for water quality, drinking water, aquatic biodiversity, and others (I have not recently done an extensive review of all existing water database, so I’ve definitely missed some). But I don’t think anybody would argue that this data is complete enough over space and time to provide a reliable measure of things like “watershed health” (if anybody could agree on how that is defined), or transparent enough to effectively integrate across basins. Water data is costly to collect, and has many complexities that make it technically difficult to manage. This is one reason that it is hard to evaluate the environmental outcomes of many water policy programs.

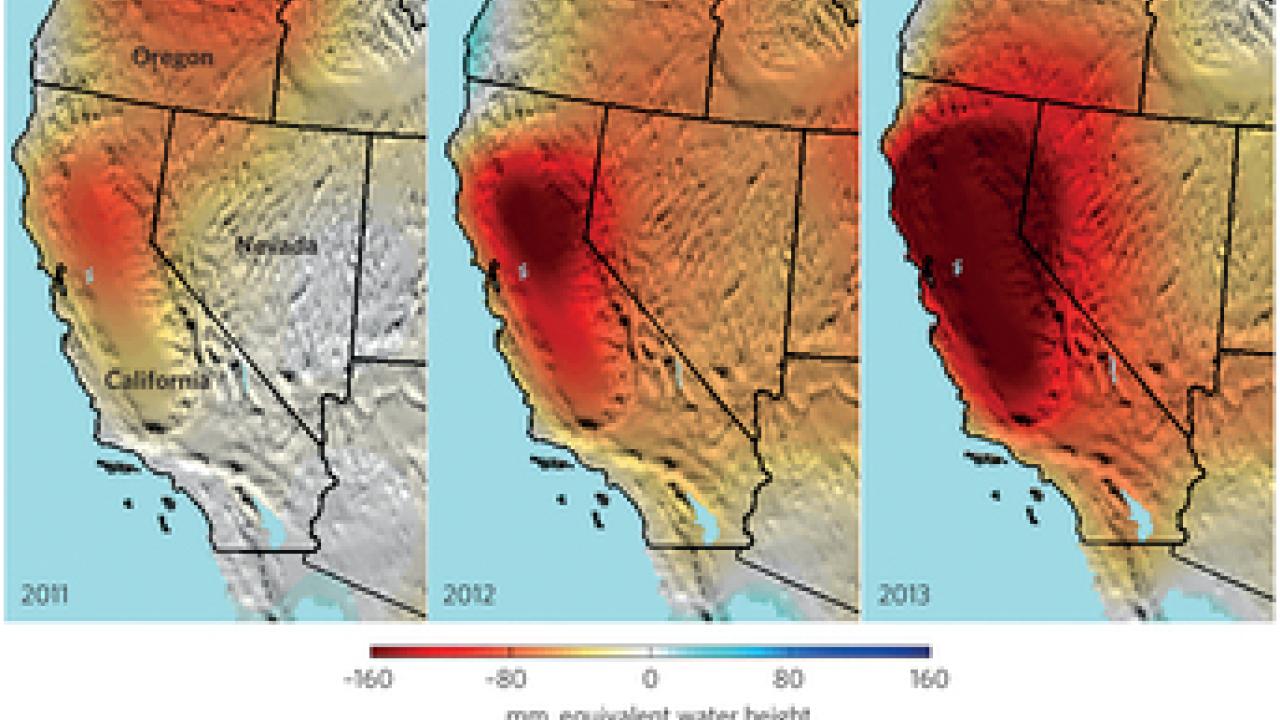

However, even if I had magic powers to remove all these barriers and suddenly make water data available to the extent desired by these observers, it would not solve water problems. Most water problems involve incentives for unsustainable behaviors, and these incentives are independent of the data. Consider groundwater, which is a classic common-pool resource that illustrates the “Tragedy of the Commons”. As has been well-documented(the figure comes from this paper), California and other global groundwater basins have experienced massive declines in groundwater levels especially in the face of drought. Even if we knew the exact geology of all California groundwater basins, the recharge rates, and how many wells are pumping water at different rates, there is still a major risk for groundwater overdraft. Every groundwater user has an incentive to continue pumping at their desired rate, and free-ride on the conservation efforts of others. This is the fundamental collective dilemma driving groundwater overdraft, and information does not change it. All water problems feature similar incentives for unsustainable behavior.

To solve problems like this, you need management institutions that change the incentives to encourage cooperation. California has recently embarked on major experiment in institution building with the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act of 2014, which requires the development of groundwater sustainability agencies and groundwater sustainability plans. In theory, these management plans will include provisions to monitor groundwater at the level of individual wells and incentives to decrease pumping rates to sustainable levels or provide funding for increasing supply. Information and water data will certainly be a key ingredient in this effort, but it is not sufficient to change the underlying incentives.

Water is not the only environmental issue in which the distinction between information and behavioral incentives must be emphasized. Take climate change. We have very good data on country-level emissions, and local-level projections of climate impacts such as temperature, precipitation, and sea-level rise. But this information has not changed the basic cooperation problem facing countries at the international level; even the recent signing of COP21 unlikely to reduce carbon emissions enough to avoid the worst impacts. Climate change information also does not change human psychology—there are plenty of climate deniers out there despite nearly universal consensus among scientists that human activity has increased climate change. What about responding to extreme events like hurricanes, droughts, earthquakes or other environmental disasters? Even if I waved my magic wand to create environmental models that provide 100% forecasting accuracy, there would still be people who suffer because they do not receive the information, or do not believe it, or have incentives to engage in maladaptive behavior (e.g.; Federal flood insurance). Information alone cannot fix these fundamental problems in human decision-making, behavior, and institutions. This is one reason that social science is a crucial partner with the biophysical sciences in solving our most pressing environmental problems.

Disqus Comments