What is Science Governance?

As a member of the Delta Science Program's Science Advisory Committe, I'm currently engaged in a planning process called the "Science Needs Assessment" (SNA). The goal of the SNA is develop recommendations about how to shift the Delta science enterprise more towards a model of "anticipatory governance", which can better identify future Delta management issues (e.g.; climate change) and develop policy-relevant science and research to address those issues. Thus the SNA involves the question of science governance, which requires examining the institutional rules that structure how Delta science is conducted. Within this context, it is important to recognize that the Delta science enterprise is inherently polycentric, with many different types of actors participating in multiple forums in which science is being developed and linked to policy.

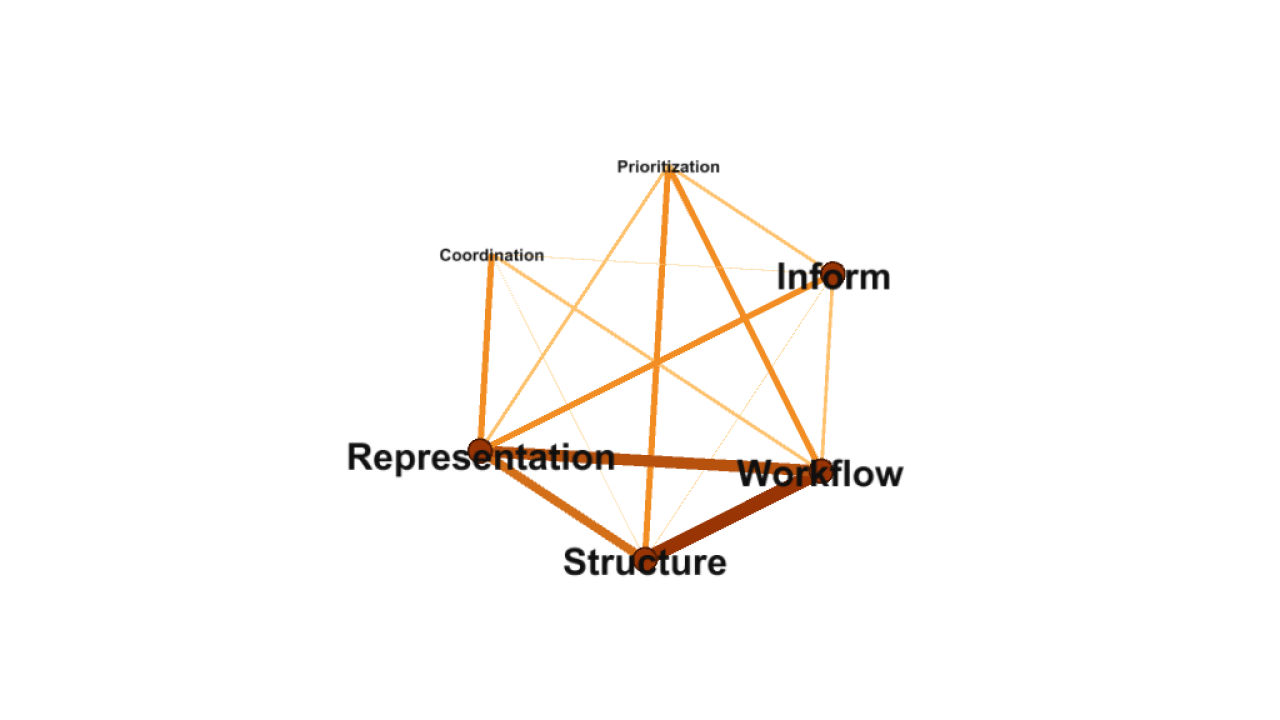

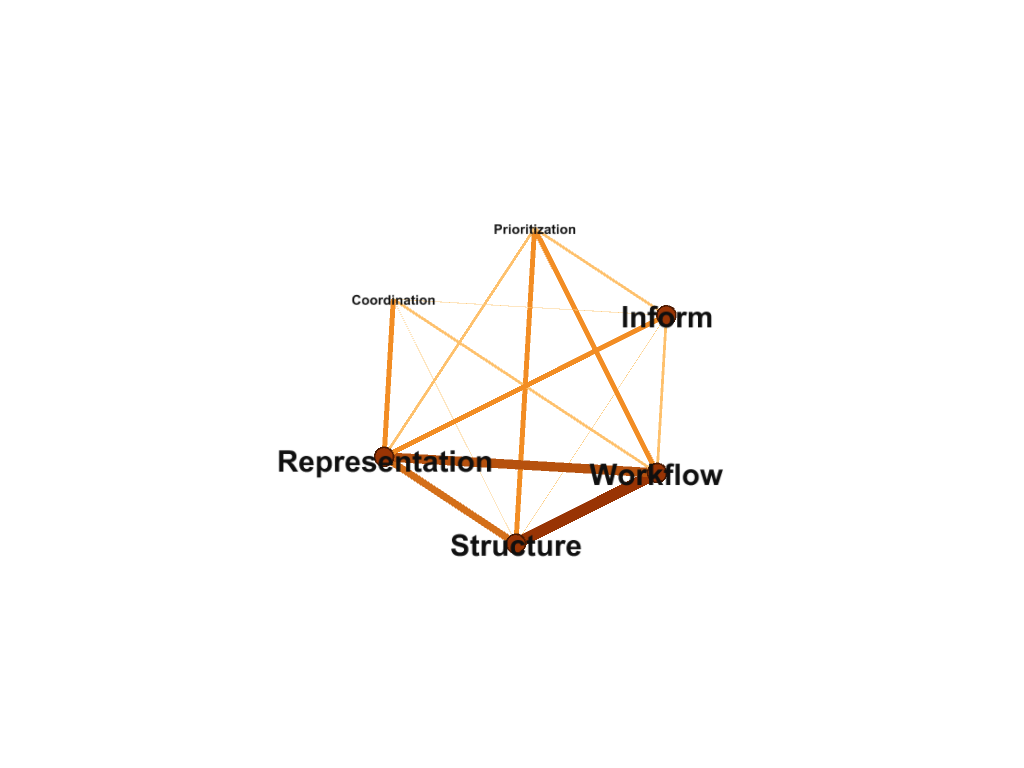

But what really is "science governance" from the perspective of stakeholders? To address this question, the SNA group held one workshop that invited Delta stakeholders to discuss the challenges and solutions of science governance. We used "Mentimeter" to implement a real-time survey, which included the prompt "Please define science governance" and received 23 written answers. To elucidate the implicit definition of science governance from these answers, I used a "mental model" approach where I first coded the core concepts that appear in these definitions and then identified the number of times the concepts co-occured in each definition. For example, if the concepts "workflow" and "structure" appeared together in one definition they are considered co-occuring. The concepts then become nodes in a mental model network, and the co-occurences are the edges.

Based on this, I identified 6 core concepts:

- Structure/Process: Governance is an institutional structure that shapes the process of decision-making with respect to science. Policy scientists typically think about institutional structure as a set of rules, which means the devil is in the details about what exact rules there should be.

- Inform: Science should effectively inform policy and support decisions.

- Prioritization: Governance should prioritize the research questions and issues.

- Coordination: Governance should coordinate across groups of actors; a key process.

- Workflow: Governance should link various aspects of the scientific workflow, e.g. models and data integration. I pulled out workflow as a specific item because respondents often mentioned concrete aspects of science such as data.

- Representation: Governance defines the group of people or organizations who have the authority to shape decision-making.

The picture below shows the resulting mental model. The nodes and label sizes are scaled by number of connections (total degree), and the width of the lines represent how many times the concepts co-occur. Structure, representation, inform, and workflow are the most central concepts. Coordination and prioritization are less frequently mentioned. In my opinion four of these concepts are governance functions: prioritization, inform, coordination, and workflow. Two of them are structural choices: representation and institutional arrangements. Science governance is thus a system that has a particular structure, which facilitates a set of desirable functions. Most people would probably agree on the desirability of the functions, and that structure in some fashion does shape function and therefore this system can be actively steered.

But the problem is, what structure? The written definitions do not identify the structural choices; it is our job as policy analysts and practitioners to consider the range of possible structural choices and map how different institutional arrangements produce different functions. The choices are not easy, and neither is the analysis. The institutional structure question is about the rules shaping scientific decisions and how they are linked to policy--how do we decide what problems and projects to prioritize? How do we decide on the way funding is allocated? How do we establish scientific workflow processes that maximize data and model integration? How do we create a pipeline from science to policy, such that policy-makers are aware of and using the best available science and scientists know what questions policy-makers need to have answered? These are some key structural questions that need to be addressed.

The question of representation is perhaps more difficult, and is often one that is overlooked in the discussion of structure. Representation is about who gets to participate in science governance, who has the authority and leadership. Hence, representation is about voice and power and nobody wants to be left out. Representation also invokes questions of equity and procedural fairness. There is definitely a zeitgeist in academic and practitioner circles that favors "collaborative science" or some version of "co-produced" or "bottom-up" science, which seeks to have "everybody" involved. But this creates a coordination dilemma, because having everybody involved makes it difficult to actually steer the system. Hence, science governance must balance appropriate representation and engagement, with having legitimate leadership than can actually make decisions and allocate resources.

The Mentimeter poll also asked stakeholders to identify solutions to science governance challenges. Two very common solutions were to increase stakeholder trust and encourage leadership development. These are two process-based goals that are crucial to the governance functions articulated in the definition. The most common structural recommendation was the creation of a joint federal-state partnership for expanding the scope of the Delta science program. Right now, the Delta Science Program is purely the creature of Delta Stewardship Council, a state agency that was created by state legislation. The science being done by federal agencies, and the funding to support it, lives at places like the USGS, USFWS, and other agencies. Knitting these such programs together requires high-level legislative and executive action at both the state and federal levels, which in turn requires current Delta science stakeholders to communicate and advocate with political leaders who lack a deep understanding of science governance and face many competing policy agenda priorities. On the federal side, the vacillating ideological goals of different presidential administrations (e.g., Obama to Trump to Biden) always makes sustaining such partnerships difficult because any institutional arrangements are potentially vulnerable to political meddling. Also, California has previously tried a federal-state program: CALFED. CALFED actually fell apart in the end, and there is much debate about its overall effectiveness. For example, we have argued that CALFED is an example of "success despite failure" and at least some of the success is due to a new set of collaborative relationships around science and substantially increasing the overall knowledge base about Delta management issues. Hence, at the very least it is worth re-examining how CALFED addressed these broad questions of science governance. Furthermore, we must also look to examples from other large-scale ecosystem management programs: the Puget Sound Partnership, Chesapeake Bay Program, Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan, Great Lakes, Gulf of Mexico, etc. These ecosystems have different approaches to the institutional structure of science governance, and many people think these programs are more advanced in terms of linking state and federal program, which may offer lessons for the Delta.

Disqus Comments